FSW Briefing: New Book Honors the Creative Partnership of Tom Kublin and Cristóbal Balenciaga

FSW reviews a new book about photographer Tom Kublin and his partnership with couture designer Cristóbal Balenciaga.

In this era of oversaturated digital content, analog experiences can feel exceedingly rare and hence more valuable. Physical experiences like books, fashion exhibitions, and live events are a critical way to reawaken and recenter public interest in the art and history of fashion.

Fashion and photography have a long shared history and can be considered sister arts. The roots of fashion photography lie in elaborate Victorian-era portraiture as early as the 1840s, ranging from wooden-faced pictures of society’s elite showcasing their finest garments to racier tableaux of dancers, actresses, and other denizens of the lower class.

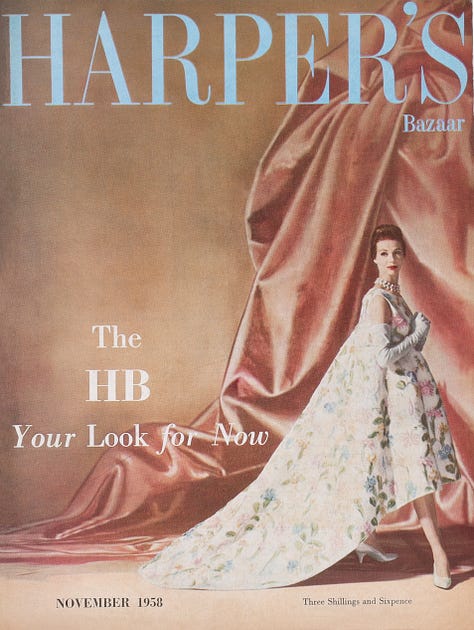

In the late 19th century, fashion editorial photography emerged in tandem with the surge in popularity of ladies’ magazines like Godey’s Lady’s Book (1830), Harper’s Bazaar (1867), and eventually Vogue (1892).

When photography curator Maria Kublin approached us last year about the book she was writing to honor her father, Tom Kublin, and his legacy as a fashion photographer and filmmaker in collaboration with legendary designer Cristóbal Balenciaga, we had to say yes.

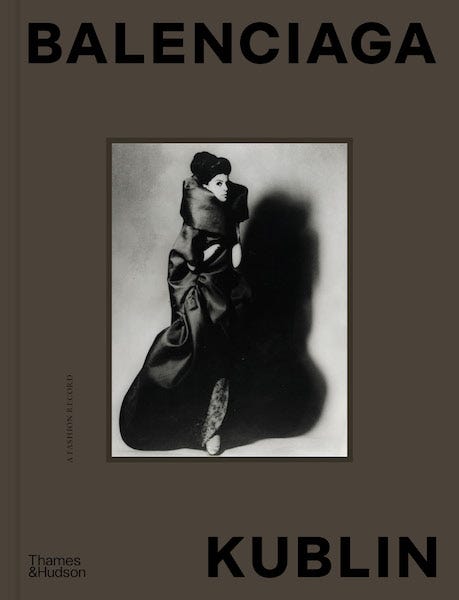

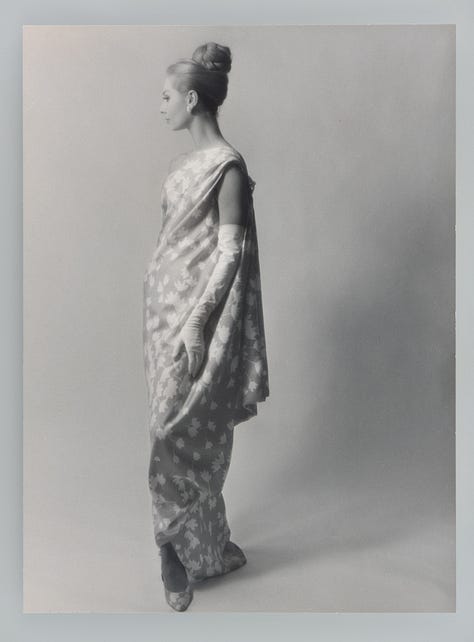

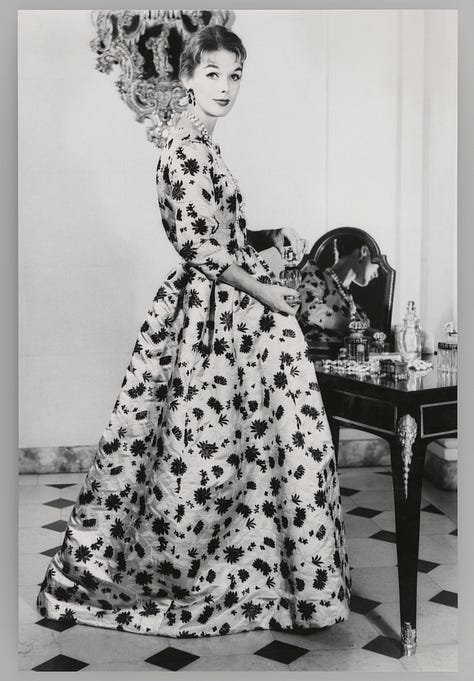

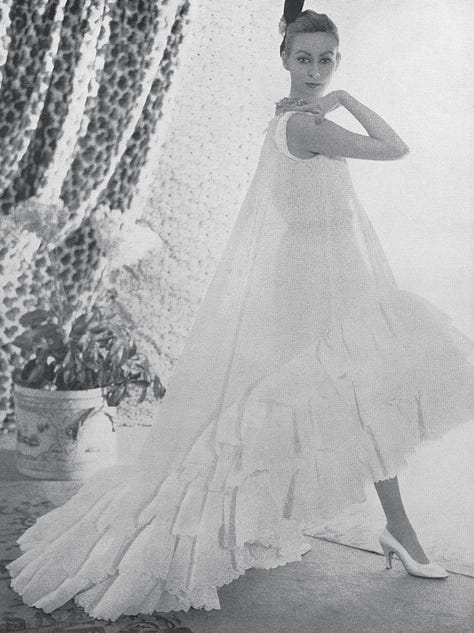

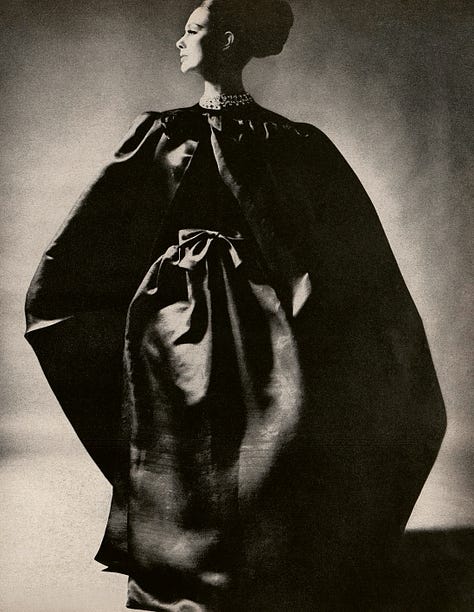

The book in question, Balenciaga - Kublin: A Fashion Record, co-authored by Maria Kublin and fashion historian and academic Ana Balda, was published last month by Thames & Hudson. It is a fascinating read chronicling Tom Kublin’s creative collaboration with Balenciaga over several decades. The book contains 163 visually arresting images and stills, mostly of Balenciaga’s signature ladylike, sumptuous fashion. Unlike many fashion books, which fall prey to the look-pretty-never-read syndrome of coffee table books, this Balenciaga-Kublin book is one you want to spend time with.

As Ana Balda’s biographical essay in the book details, visionary photographer Tamás Kublin, known as Thomas or “Tom,” was born in Hungary in 1924. By the age of 13, Kublin was already dreaming of becoming a photographer, initially against the wishes of his parents. They eventually allowed him to pursue his craft at the Budapest School of Photography. By the early 1940s, Kublin became well-known and earned roles at prominent publications like Fotoélet and Fotoriport. During World War II, he served in the Hungarian army as an official photographer. After the war, Kublin opened a photography studio in Zurich and began working on advertising campaigns. According to Balda, an article in Harper’s Bazaar notes that Kublin’s passion for fashion photography began with an assignment he received to cover a show in St Moritz by French couturier Jacques Fath.

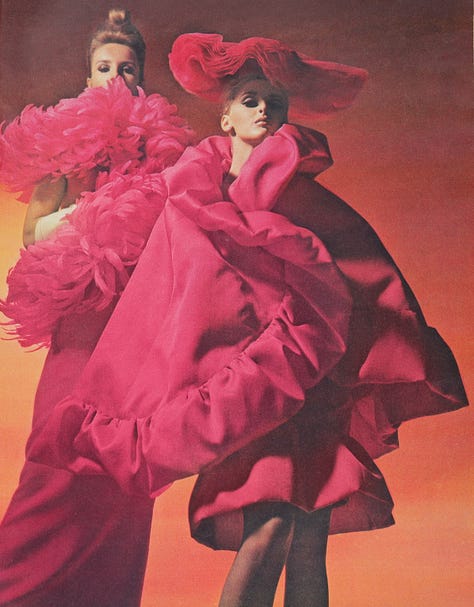

The creative collaboration between Kublin and Balenciaga began in an unlikely place: the shooting of a portfolio of samples for Abraham, a Zurich-based textile supplier that worked with all the leading haute couture houses. According to Balda, from 1953 til Kublin’s death in 1966, Abraham commissioned Kublin to take hundreds of photographs for dozens of collections for “Fath, Rochas, and Pierre Balmain to Christian Dior, Givenchy, Lanvin, Chanel, Yves Saint Laurent, and, most frequently, Balenciaga.”

The boom of post-war fashion transformed the fashion industry and brought fashion photography to new prominence. Well before the war, however, Cristóbal Balenciaga rose to fame in 1937 with his debut collection and soon became the darling of major publications like Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue into the 1950s.

Oddly, the very modern problem of fashion fakes or authorized copies of haute couture designs is what ultimately formalized Balenciaga and Kublin’s partnership. Since the 19th century, the luxury industry flourished due to elaborate licensing agreements that allowed couture designs to be replicated and retailed in high-end stores around the globe. As Balda notes, this practice “inevitably led to the rogue trade of illegal copies.” To safeguard their IP, haute couture houses hired fashion photographers to take photos as records of each collection. It was in this capacity that “Balenciaga appointed Kublin to take pictures in this category between 1955 and 1966.”

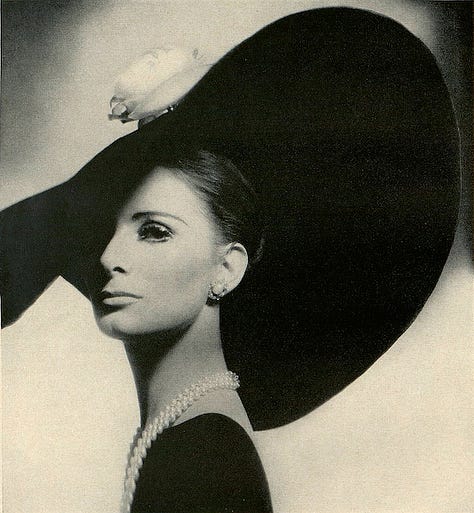

Over time, Balenciaga and Kublin grew close. Their partnership extended into more creative projects, including films. Kublin became a creative ally and a trusted confidant who formed an essential role in preserving and protecting Balenciaga’s legacy and timeless designs.

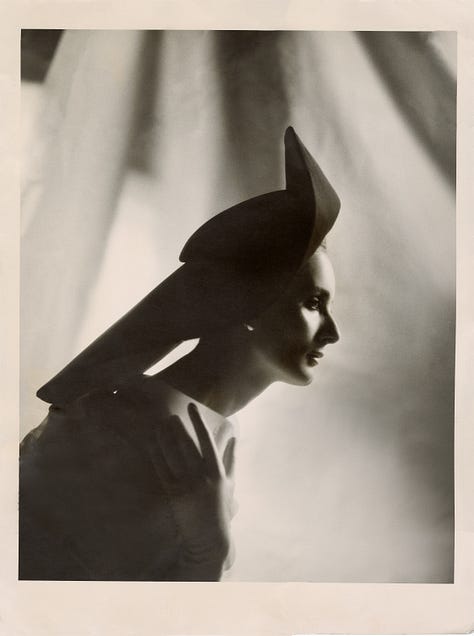

As an artist, Tom Kublin was more than just a photographer. He was also a filmmaker and a skilled draughtsman who sketched each photograph before he shot it. Kublin’s work reveals a sophisticated understanding of form and perspective and takes inspiration from other artists, including Mondrian, Goya, Bellini, and Velázquez.

Some of the most exciting parts of Maria Kublin and Ana Balder’s book are the most personal ones. In addition to Balder’s in-depth essay on Tom Kublin and Balenciaga, the book includes an interview with Maria Kublin’s mother, Katinka Bleeker, a model, former Miss Holland, and photographer who became Tom Kublin’s muse. There also is a fascinating inset, “Letter to Tom,” from Italian fashion photographer Gian Paolo Barbieri.

Of course, the main body of the book comprises 163 images and stills of Kublin’s work across the decades, including behind-the-scenes images of his studio and workspaces that show the intricate process behind his artistry. From a branding perspective, Kublin’s photographs established a core visual identity for Balenciaga’s timeless designs and, in turn, helped secure and preserve the designer’s place in fashion immortality.

Kublin and Balda’s book is more than simply an exercise in recounting fashion history or narrating a retrospective account. The volume is a fitting tribute to Kublin’s talent and artistry, his unique partnership with Balenciaga, and their shared legacy in the pantheon of fashion creatives.