Dress History as Fashion Strategy: An Interview with Dr. Kate Strasdin

FSW talks with Dr. Kate Strasdin about her new book, her narrative strategies as a writer, and how luxury brands are preserving the artisanal nature of fashion.

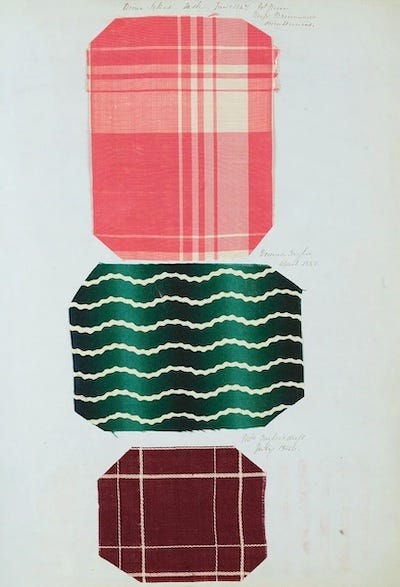

Dr. Kate Strasdin is a Senior Lecturer in Cultural Studies at Falmouth University. Her second book, The Dress Diary of Anne Sykes, which was published earlier this year by Pegasus Books, is a portrait of the life of a Victorian gentlewoman, Anne Sykes, told through scraps of fabric kept in a notebook or “dress diary.” In the book, Strasdin weaves together Anne’s story and that of the important people in her life against a mosaic of life, culture, and trends in mid-19th-century England. Perhaps more interestingly, she narrates her process of discovery as a historical detective and researcher, faced with the seemingly impossible task of tracing the origins and ownership of a mystery notebook through pieces of fabric and notes in the margins.

FSW sat down with Strasdin to find out more about her book, as well as to discuss her storytelling strategies and the current state of fashion and luxury.

FSW: How did you initially get interested in fashion?

KS: When I was a child, there was a fashion game that came with a tin of tea. For each one, you would build up this kind of theme of cards and then you would stick them in this little book that you could send off for…. And I collected those and thought, oh, my God, the way people looked was so different. And then I realized that there were museums that kind of did this sort of thing that you could go and see these things. And so when I was 14, instead of having roller disco parties for my birthday, I was going to textile museums, which I'm sure my friends were thrilled about. And then I did my BA in history but didn’t specialize. I'd done some volunteering in a historic dress collection near me and thought, This is amazing, I love it. But I didn't know how it was going to be a career.

Then I eventually specialized, doing a course in the history of textiles and dress at Winchester School of Art. And it was a much more object-based course. So you had the Courthold, which was very art history-based, using dress as a kind of tool to look at dating paintings. But this course was much more practical about using objects, which appealed to me. And so it went from there. And then I did my PhD when my kids were tiny and I did it at home part-time and just kind of fell into teaching part-time from then.

FSW: Was it difficult doing a PhD when your kids were little?

KS: The funny thing was my eldest son was at nursery, so he was three, and my youngest son was a baby. I started when I was pregnant with him. But you know what it kind of offered me because it was part-time and I would just do a few hours a week and it gave me sanity. When he was asleep, I would just do some research. And I found it made me feel like myself again, rather than just like that's amazing.

FSW: How did you come to own the diary of Anne Sykes and decide to write a book about it?

KS: Yeah, I think it's such a lovely story about female networking. I started to make lace. Specifically, it was Honiton lace, a handmade lace from Devon, the particular part of England that I'm from. I started making it not long after I was married. So, 25 years ago, as a kind of local craft, I wanted to make something that came from where I lived. When my kids were small, I started going to this monthly group nearby, just down the road, on the first Saturday of every month. The women that ran it hired a hall and then it was just women, around 50 or 60 of them, mostly much older than me. We'd all sit around tables, making lace, drinking coffee, and chatting about what was going on in our lives.

It was therapeutic. I loved it as that kind of exit from family life just once a month. The ladies that ran it knew that I taught about fashion history and textiles, and so now and again I would give just a mini kind of presentation to the group about an aspect of things that I did. And it was after one of these little talks that one of the ladies who was in her 80s called Francine came up to me and said that she had a ton of stuff in her apartment that she was getting rid of and she was downsizing. Would I like to go down? I think she didn't want to go through the kind of complexity of having to be in touch with museums or organizations. What I didn't know was that she was terminally ill and she was just kind of rationalizing the rest of her life. Her family wasn't interested in the things that she had left. And so I went down there and just had this amazing afternoon. I didn't know her very well at all, but just had this amazing afternoon of her storytelling about the things that she had and her giving me things, including dress patterns and some garments that I gave to a couple of local museums.

After I’d been there a few hours, [Anne Sykes’ dress diary] was the final thing that Francine pulled out of a trunk at the base of her bed. It was this object that was wrapped up in really soft brown paper. It had been there forever. It was one of those kind of spine-tingly moments. When I unwrapped the brown paper, there was this very old book covered in bright pink silk bulging with something. And I just had a moment where I thought, this looks amazing. Lo and behold, it was just this ledger filled with thousands of scraps of fabric with small captions above it. But, Francine knew nothing about it. She'd acquired it in London in the 1960s, and it was a complete mystery. It was anonymous.

While I was doing my PhD, I kept dipping into it but I had other things to do. And then eventually, thanks to the pandemic, I had the time to just sit and start making my way through it.

FSW: One of the most striking parts of your book is when you discover Anne's identity. What was that like?

KS: At first, it was all very piecemeal…. So I figured the easiest thing I could do between running my kids here and there and everywhere was to just gradually transcribe each of the captions and see what crops up.

I can remember I was on my own. My husband was out at work one evening. My kids were in bed…. I just thought, well, I'll just sit down for a bit longer and work my way through. Then I came across this one caption where [Anne Sykes] identified herself as a kind of keeper. It was such a moment that I had to ring my husband straight away…. [Then I started] thinking, okay, maybe I can make more of this if I've got Anne and I can find her in the records, which I could once I'd got her and then her wedding date.

If I found her, then maybe I can find other people that crop up in the book as well in the volume.

FSW: How did you go through that process of investigating, documenting, and deciding how to tell Anne’s story? Specifically, why did you decide to narrate your process of discovery as a historian along with what you were uncovering about Anne’s life?

KS: It's such a story of the pandemic…. [After signing with] my now agent, I came up with this kind of vague outline of thinking…. In October 2019, the idea was that in January 2020 I would be able to make lots of research visits and delve into all sorts of different archives to be able to find out as much as I could about this time and place. But when the first lockdown happened in March my book deadline wasn't going away, … it became all about the detective work that I could do from here, from this desk, from this device.

Since I couldn't go anywhere, I started by kind of outlining the people that I’d found. I started with Anne, her husband, her sister-in-law, then her niece…. And it started to kind of spiral outwards a bit like a cobweb. [T]hen I thought, OK, if I've got these people, what does each of their story lend itself to?

For example, her niece, Charlotte. Lots of the samples in the book associated with her were printed cotton. So, I thought that [Charlotte’s] chapter could be broadly about the printed cotton industry in Lancashire at that time, as well as being about her life as much as I could tell it. And gradually, that's what it became. It became this kind of quest to find 20 or more people who feature in Anne's world. Then, attached to each of those, I needed to hook a story as a sort of microhistory exploding outwards into a macro one that explained something about the much bigger picture.

In this approach, Hannah Wrigley’s chapter became about mourning dress because she had sent Anne some swatches of clothes that she'd worn after her mother had died. It was that almost just putting out all of these people's names and thinking, right, what story best goes with them at the same time as kind of Anne's life story, being the constant connection with them all the way through. But, all of this was written from home, relying on digital archives and the kind of census records and newspaper records that I could access. That became the sort of magic of discovery when we were just locked in at home, I could venture out via this portal of my laptop and find her world.

FSW: What is your take on what fashion is doing now, both from the big brands as well as fast fashion?

KS: Having taught at an institution that holds sustainability very close to its heart has shaped a lot of my thinking about fashion. Falmouth University is in Cornwall, down in the far southwest. It has a very close relationship with the coast and with the countryside on its rural campus. Sustainability has very much been at the heart of a lot of its courses.

Increasingly, the students I've met in the last 10 to 15 years have been talking about [sustainability] from their perspective. I've learned loads from them. They've been the catalyst to me thinking differently about clothes myself and about the fashion industry. I feel the idea of valuing textiles much more robustly. I rarely buy new things now just because I love secondhand. I love buying vintage, though I don't buy a lot of it. I'm much more interested in how things are valued or should be valued.

I think that couture and the big brands often get a bad rap for various things. But I do think their protection of the artisan houses, such as the feather houses, embroidery ateliers, flower workshops, and pleating workshops, is really important.

I have tried to move away from consumption over the last 10 years and am much more mindful about it. In a way, that's where I see my Instagram [@katestrasdin]. Through it, I consume my love of fashion. I consume it through museum pieces and it's almost like a different form of consumption.

FSW: Speaking of Instagram, you are social media’s favorite fashion historian. How did you fall into sharing stories and images of fashion history on social media?

KS: Sometimes, I do silly stories or a weekend of storytelling and then post the garments to go with it. There's a lot of fun to be had with that kind of thing. I think the way you recreate those moments is such a reminder of how much fashion has evolved but also that it's still fun and that history is not boring.

In terms of social media, I enjoy the connections. I've only found social media to be positive. I rarely have had the toxic side of social media seep into my feed either on Twitter or Instagram. In the aesthetic corner of social media, be it lifestyle or fashion history, I think is generally a pretty positive place.